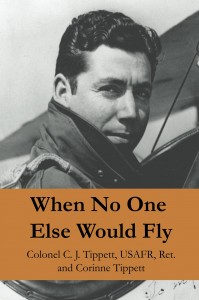

The Health Parasol was a home-built kit plane, and Cloyce Joseph Tippett flew it in 1930 – or tried to fly it. Thank you Wiki for the photo!

Before he flew a Heath Parasol home-built, Cloyce Joseph Tippett learned to fly in a Curtiss JN4 biplane in 1929. He learned from a traveling barnstormer, and by the seat of his pants, which was enough to convince him that aviation was the life for him.

Both the Great Depression, and the fact that he was only sixteen, limited his options of extending his flying ability. He had to take any opportunity that came his way to keep flying.

In 1930, Tip was headed for college and accepted his Aunt’s invitation to stay overnight on the road trip from Port Clinton, Ohio, to Detroit, Michigan.

But when Tip discovered that Aunt Daisy’s husband, Mr. Laberdee, was a mechanic with a garage full of OX5 aircraft engines, the trip to college was put on hold. Tip had his hands on the engines and was getting experience he wouldn’t find in college.

In the back of the shop, Tip found dozens of motorcycle engines that Mr. Laberdee and his fellow flight enthusiasts were putting into Heath Parasol kit planes that they were building in their spare time. It was heaven for Tip, who was considered an experienced pilot among these kit-building mechanics.

Tip’s description of his first Heath Parasol test flight in a Michigan potato field is delightful. In the soon-to-be-available book that he wrote about his flying life, he says “The home-built plane was more agile than the lumbering old Jenny and responsive to the controls. It was quite stable for the short time we were airborne.”

And then he almost crashes when the Henderson engine quits mid-air.

Tip’s perspective of the home-built planes, and the other aircraft within his reach is riveting. He was involved in a time of aviation that is a fascinating side story to mainstream aviation pioneering.

The Heath Parasol was reportedly easy to build and easy to fly, and could be assembled with materials and tools commonly found in 1920s and 30s workshops or garages. When civil aviation became organized enough to require licensing of both pilots and craft, the Heath Parasol was the only kit built aircraft that could be licensed.

The wings were constructed of wooden spars, and the airplane cover was fabric. It was powered by the Henderson motorcycle engine, or equivalent, producing 25 hp and 19kW.

Tip found that the glide path, after that engine quit, was adequate for getting back down to a potato field if required. If you’d like to read more, contact us to sign up for the book release notification. We never share your information, and we have a lot of fun aviation stories!