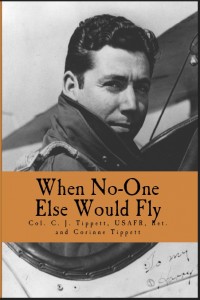

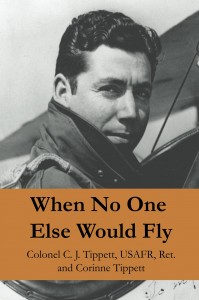

Col. C. J. Tippett trained pilots to fly the Douglas C-47 Skytrain over the Himalayan Mountain route in 1942. The pilots were Flying The Hump.

World War II pushed aviation pioneering hard.

Safety did not come first, because people were already dying on the front lines, and beyond.

War changed the rules, and aviation history is full of flights that today, would be considered recklessly irresponsible. But the flights were unimaginably heroic.

The Hump was a name that WWII pilots used for the Himalayan Mountains, and flying it in 1942 without adequate navigation, information, weather reports, and technical support was an aviation nightmare.

But American pilots, in conjunction with other Allied pilots, flew it every day for almost three years at President Roosevelt’s request.

The US had been sending American pilots and aircraft to China to fight the Japanese invasion for years on an unofficial basis. The Flying Tigers had been mercenaries, flying combat air missions against the Japanese over the Chinese mainland, until the US joined WWII and Roosevelt was able to officially recognize their efforts.

America was directly fighting the Japanese in the Pacific and supporting Chiang Kai-shek’s battle in China.

By 1942, Japan had blocked the Burma Road in addition to coastal China, and the only way to get supplies to the Chinese forces was to fly them in, over an air route that is, even today, considered extremely dangerous.

The civil aviation infrastructure was called on to provide pilots with the skill to fly this route, and the newly-formed Civil Aeronautics Administration Standardization Center in Houston, Texas, was a natural source for training.

Cloyce Joseph Tippett, then a First Lieutenant in the Air Corps Reserve, was the Senior Advanced Flight Instructor at the Houston Standardization Center, and he also had plenty of flight time in the Douglas C-47 Skytrain, the aircraft assigned to the effort.

Tip trained pilots specifically for the conditions they would encounter on the route, and certified them for mulit-engine flying in the C-47.

Tip had been flying a CAA owned DC-3 for years and he was already known for his commitment to flight safety. Tip believed that preparation and training were the key. If the risk had to be taken, then the pilots had to be certified in instrument flying, multi-engine flight, and every kind of navigation possible. So he got to work.

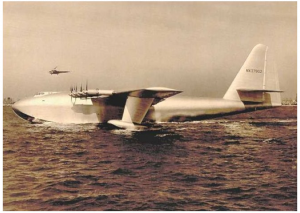

The C-47 Skytrain was a version of the Douglas DC-3, the most reliable aircraft of the age. The C-47 had a reinforced floor and cargo door, making it more suitable for supply runs. But even so, the altitudes that pilots had to fly to get through and over the Himalayan Mountains were pushing the C-47’s design limits.

Additionally, the aircraft were often overloaded at take-off, and unpredictable weather forced pilots to push fuel ranges to skip flooded landing strips.

The crash rate was heartbreakingly high, but the pilots continued to fly the route, and the C-47 Skytrain performed admirably until finally replaced by larger, more suited aircraft.

In today’s aviation world of GPS navigation, constant radio communication, and multi-layered safety protocols, the conditions that routinely faced pilots flying the Hump were astounding… and unacceptable.

But not only did the pilots, crew, and support staff of the 1940s accept the conditions, they met the challenge and paid the price.

Some of the most courageous aviation pioneering took place there, and their stories are riveting. Tip was proud of the pilots he met and trained, and considered them his personal heroes.